© Mark Hertzberg (2023)

Frank Lloyd Wright is known by many people only for his domestic architecture. But some of his undisputed masterpieces were public buildings. One was the sprawling Imperial Hotel in Tokyo which was 76,865 sq. ft. in an area which measured 156,442 square feet. The hotel, which opened 100 years ago this month, was demolished in 1967-1968, despite an international outcry which included efforts to save it by Olgivanna Wright and Edgar Tafel.

The lobby and entryway were saved and rebuilt at Meiji-mura, a large park with buildings of diverse architecture from the Meiji era (1868 – 1889). It is near Nagoya, several hours from Tokyo by Shinkansen (bullet train), local train, and bus.

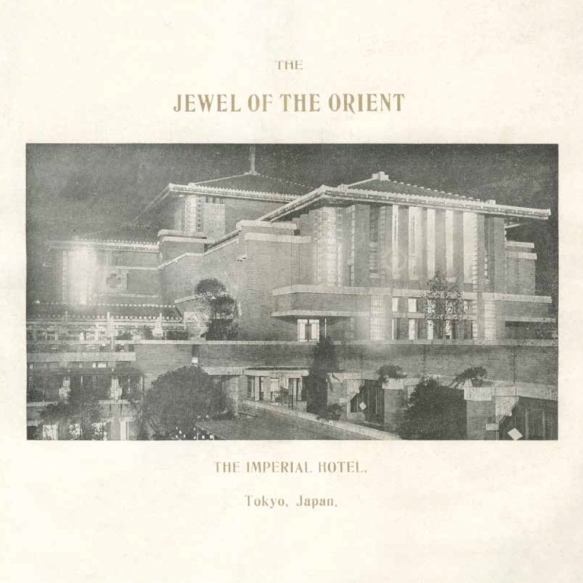

The scholars and archivists at Organic Architecture and Design (OA + D), including Kathryn A. Smith, have made two new significant contributions to our understanding and appreciating the breadth and scope of Wright’s Tokyo tour de force. In 1923, concurrent with the opening of the hotel, the management published The Jewel of the Orient, a richly illustrated 32-page brochure about the building and its amenities. The narrative was written anonymously, and takes the reader on a walking tour through its public places and service areas. OA + D has republished the brochure, with an introductory essay by Smith. Only 500 copies were printed, it is a bargain at $20.00:While one can visit the remnants of the grand hotel at Meiji-mura, the OA + D republication of The Jewel of the Orient is a stark reminder of what was lost when the first wrecking ball struck and breached Wright’s hotel. What the Kanto Earthquake on opening day and the bomb couldn’t take, the wrecking ball did.

https://store.oadarchives.org/product/jewel-of-the-orient-the-imperial-hotel

On the back cover, the writer describes the hotel as “Neither Of the East Nor Of The West, But Might Fittingly Be Called A Blending Of The Ideals Of The Two Civilizations.” He (presumably) quotes an unnamed “Writer of International Fame” describing the hotel “As A Symphony In Brick And Stone.” It certainly was.

The 1923 black and white photographs are illuminating, particularly the double truck (one photo over two facing full pages) on pp. 14 – 15, an overhead view of the complex. The collection of photographs reinforces the wonder of how one man could design such an intricate and complex masterpiece, especially in the pre-computer age. It has been written that Wright conceived of such landmark buildings as Midway Gardens and Fallingwater long before he “shook them out of his sleeve” and articulated their design on his drafting table. We can only wonder how Wright imagined the Imperial Hotel before drawing it. Because there had to be plans for each hotel ornament, as well as the china and the furniture, and not just plans for the building itself and its ancillary structures, Smith wrote me, she estimates that there may have been between 2,000 and 3,000 drawings made. Only 822 drawings of the hotel survive in the Wright archives at the Avery Library. Consider the volume of drawings, at least one for each element of the hotel:

As for the furnishings, the author of the brochure notes “The thing which strikes one most forcibly on entering any of the rooms, be they parts of a suite or otherwise, is the absence of ready to buy wares.” Everything was “especially designed and made for the hotel…conceived by the mind of a master and manufactured with a view to forming integral parts of a completed and harmonized whole…”

Film 100 years ago was infinitely less sensitive to light than today’s digital cameras which can take pictures even under dark conditions. The anonymous photographer capably used natural (ambient) light in many interior photos as well as lighting others. There are photos of lesser known aspects of the hotel including the Arcade shops in the basement and the reading room. A post office as well as a branch of the Japan Tourist Bureau were also in the hotel. Hotel staff members took English lessons in the Service School (nine-tenths of the complaints to management over the years in the prior Imperial Hotel had been about guests and staff having difficulty communicating with each other). Look at Wright’s use of indirect lighting in the (reconstructed) lobby:

Smith writes it is “surprising” that the writer of the brochure “not only sensitively describes Wright’s architectural accomplishments, but he also emphasizes the technological progress represented in everything hidden from sight. There are not only descriptions, but photographs of the mechanical rooms.”

Wright, who many think was loathe to collaborate with anyone, had hired a Chicago company and a mechanical consultant to oversee electrical machinery for the hotel kitchen and service facilities. Meals could be served to 3,000 guests at a time. There are photographs of the “huge electric Blakes-Lee dish washing machine capable of cleaning and drying 5,600 dishes in one hour” and one of the four “large Tahera autonomic (silver) burnishing machines.”

The photographs of the powerhouse, laundry, and ice plant are of particular historic importance because they were destroyed in the Allied bombing of the hotel, May 25, 1945. The Banquet Hall was also destroyed. Although the Allies rebuilt it in 1946, the work was not executed to Wright’s design.

Wright relentlessly spent months “testing and rejecting the texture and color of the brick, just like a Japanese tea master choosing the perfect ceramic cup for his ceremony,” writes Smith. Only appliances were ordered out of a commercial catalogue. The indirect lighting, indeed all aspects of his design, she writes, were “certainly in sympathy with omotenashi, a subtle Japanese concept of hospitality and personal behavior.

The writer of the brochure takes note of the furniture and fixtures in the hotel. “They were conceived by the mind of a master and manufactured with a view to forming integral parts of a completed and harmonized whole,…possessing all the characteristics to be found in a home of refinement and culture.” He observes that the guest rooms are “convenient” to the public areas. “This feature is what has caused many to declare that the Imperial Hotel is not a single structure but the systematic and convenient grouping of a number of structures that go to form a community in themselves.”

I chuckled when I read about the barber and beauty shops in the basement in her essay. I recalled that my parents stayed in the hotel in 1957. They never mentioned Wright to me (I was not quite seven at the time). My mother kept a diary during their trip to Japan. Her only remark about the hotel was that she had her hair done there while my father was in a business meeting.

A curious phrase in the text of the brochure implies the author was writing, at least in large part, for an American audience. While describing “The Ground Floor” in his walking tour of the hotel, he notes, “The prohibition craze has not invaded Japan as yet and the Imperial Hotel has provided a place where friends may meet after the day’s task is done and enjoy one another’s society over an anti-Volsteadian cup (emphasis added).” This references The Volstead Act, the law that created Prohibition in the United States.

It is not surprising to read in Smith’s essay of the “conflict between commercial value versus cultural value” of the hotel, and that the budget eventually quadrupled. The first page of the 1923 text notes “The apparent indifference of the management to the cost of hammered copper, brass, gorgeous upholstering and the like, all bring down the wrath of the dividend seeker on the heads of the director, who approved of the structure, the architect who conceived and designed it and the builders who dared to construct it. To them the new Imperial Hotel is a masterpiece of folly, a source of never ending expense and a case where pride took the bridle in its teeth and ran away with judgement and common sense.” Aisaku Hayashi, the hotel manager who hired Wright, was forced to resign.

The hotel was arguably “The Jewel of the Orient,” as evidenced by the cover photo. The hotel is shining at night with Wright’s artful use of indirect lighting. Smith’s closing remarks address the photo. “The building looked like a glowing beacon and could be seen from miles around. It not only stood for technological progress, but for the architect’s humanistic view of how architecture could express a spiritual dimension. While it stood, it also had great meaning as Wright’s effort to embody omotenashi.”

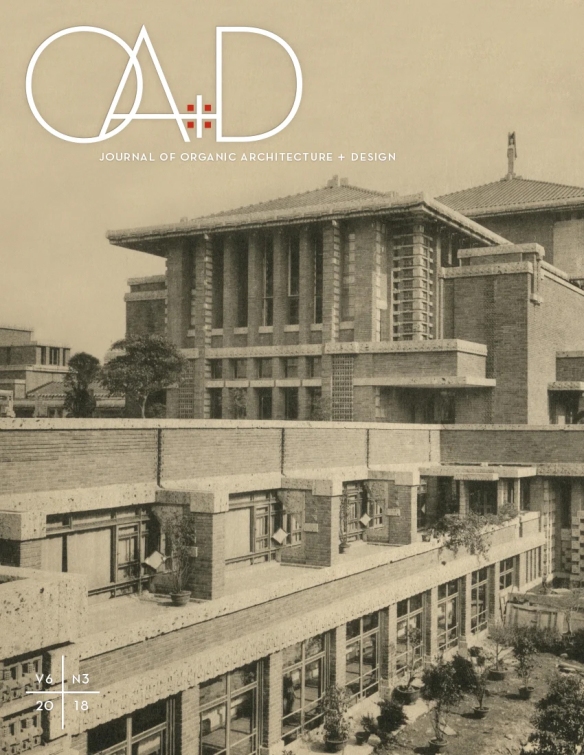

Every issue of the OA + D Journal of Organic Architecture and Design is devoted to a single topic. The new issue, titled “100 for 100,” is 120-pages edited by Smith. It showcases 100 objects from the hotel’s history. The objects, some of which are being published for the first time, come from the OA + D archives:

https://store.oadarchives.org/product/journal-oa-d-v11-n2

It is Smith’s second Journal about the hotel. The previous Imperial Hotel issue, published in December 2018, is well illustrated with construction photos:

https://store.oadarchives.org/product/journal-oa-d-6-3-pre-order

I photographed the rebuilt portions at Meiji Mura in 2018 and enjoyed a drink in the coffee shop above the lobby:

https://wrightinracine.wordpress.com/2018/12/06/imperial-hotel/

https://centrip-japan.com/spot/meijimura.html

Some of the last photographs in my web piece show the unfinished and very raw rear of the rebuilt portion of the hotel, underscoring the inevitable destruction of the greater hotel in 1968. The rear of the building mocks us, making us think that what we saw inside and from the front was a Hollywood set. I wrote above the photos, “But, what about the rear of the structure? I had to look, but it was a bit like peeking behind the Wizard of Oz’s curtain.”

A new Imperial Hotel was built after Wright’s was demolished. The hotel website asserts that there are plans to rebuild the 1923 main building and “merge” it with the modern hotel. In the meantime, the hotel, in partnership with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, now incorporates “Wright-inspired motifs, patterns and designs into the furnishings of its current buildings.” And, for $10,000 a night you can stay in the Frank Lloyd Wright Suite, “the only one in the world (which) features an Oya stone relief, handmade stained glass and oak furniture staged in the symmetry for which Wright was famous.”

https://www.imperialhotel.co.jp/e/tokyo/special/wright_building/

No, thank you, that’s not for me, not after seeing the real thing in the century old photographs in The Jewel of the Orient.

OA + D Home Page:

Please scroll down for previous article on the website.